Ravenna Festival

This year's theme: Ex tenebris ad lucem (S'l'è nöt u s'farà dè)

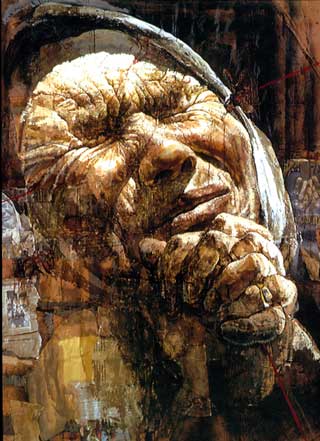

The 2010 edition of Ravenna Festival centres on the themes of night and darkness in all their different shades of meaning, which somehow always refer us to the Zeitgeist. And the “spirit of our times” seems less inclined to Aufklärung (Enlightenment) and humankind’s magnificent, progressive destiny than to the nocturnal odes of wandering shepherds, if we can borrow imagery from Leopardi’s verse. The connected metaphors of wandering and shipwreck underlie the main theme and strike another essential and revealing background note. Darkness is lack of light and thus – metaphorically – blindness. Darkness means night, death and physical, intellectual, moral blindness. Darkness means opacity, as opposed to the transparency of light. Darkness is infernal; light is divine and celestial. And yet, in Western art, darkness gives birth to the most wonderful images: the idea of darkness is associated to sleep, and Francisco Goya’s disturbing “black paintings” “showed” us how the sleep of reason produces monsters. In turn, sleep is associated with dream and nightmare. Darkness also means separation from God – but it is in the dark that the visions of such great mystics as John of the Cross or Saint Teresa of Avila appeared. In Western cosmogonies, the separation of light from darkness is the founding act of the universe itself. According to Genesis, with this very act God created the cycle of day and night, and therefore created time. God’s “Let there be light” shaped the whole of Creation, and light was made out of pitch darkness, which was there when light wasn’t.